Think of your building as having a silent, always-on bodyguard. That’s passive fire protection (PFP). It’s not the fire alarm that shrieks or the sprinkler that bursts into action; it’s the very fabric of the building—the walls, doors, floors, and specialist seals—all working together to contain a fire where it starts.

Passive fire protection is best thought of as the building’s built-in resilience to fire. It’s a fundamental part of a property’s fire safety strategy, woven directly into its construction. Unlike active systems that need a trigger, PFP is constantly on duty, providing a permanent shield against the spread of fire and smoke.

This guide is for UK landlords, business owners, and property managers—anyone who holds legal responsibility for fire safety. Understanding PFP is not just about technical details; it’s a core part of your duties under the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005.

The main job of passive fire protection is to compartmentalise a building. Imagine dividing your property into a series of secure, fire-resistant boxes. By using fire-rated walls, floors, and doors, PFP achieves several critical goals:

Properly designed and maintained PFP is non-negotiable for protecting lives and ensuring your business can recover from a fire. Its importance is clear when you look at the numbers: the UK passive fire protection market is booming and is projected to be worth over £200 million by 2033. This growth, highlighted on platforms like Grandviewresearch.com, is driven by stronger regulations like the Fire Safety Act. For any property manager, a robust PFP system is not just good practice—it’s a legal and moral duty.

It’s a question I hear all the time from property managers and business owners: what’s the real difference between passive and active fire protection? It’s a common point of confusion, but understanding how these two systems work separately, and more importantly, together, is fundamental to your building’s safety and your legal compliance.

Think of it like this. Active Fire Protection (AFP) systems are the loud, obvious emergency responders. They spring into action when a fire is detected. A smoke detector sends a signal, an alarm bell rings, a sprinkler head bursts to life. These are the systems that react. They need a trigger to do their job.

In complete contrast, Passive Fire Protection (PFP) is the silent, ever-present fortress. It’s physically built into the very fabric of your property and works 24/7 without needing to be “switched on”. PFP is all about containing a fire, smoke, and heat within a specific area for a set amount of time. One system detects and reacts; the other resists and contains.

A genuinely robust fire safety strategy is not about choosing one over the other. It’s about ensuring both work in perfect harmony. The early warning from an active system is only useful if the building’s passive systems are holding back the fire to give people a protected route to escape.

PFP provides the fundamental structural resilience that makes a safe evacuation possible. Without effective fire compartmentation, an active system’s warning could be severely undermined as fire and smoke might spread uncontrollably through a building.

The goal is to buy time. Time for people to get out, and time for the fire brigade to arrive. The concept map below breaks down the three core functions of passive fire protection.

As you can see, PFP is focused on containing the fire, protecting the building’s structure from collapse, and creating that invaluable window for evacuation. Each element is another layer in the safety net.

Let’s look at how this all plays out with a side-by-side comparison.

The following table breaks down the core differences between PFP and AFP, showing how their distinct roles contribute to a comprehensive fire safety plan.

| Attribute | Passive Fire Protection (PFP) | Active Fire Protection (AFP) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | To contain fire and smoke, protect escape routes, and maintain structural integrity. | To detect a fire, alert occupants, and actively suppress or extinguish the fire. |

| How It Works | Physically built-in materials that resist fire. Always ‘on’ and requires no activation. | Systems that require a trigger (e.g., heat, smoke) to activate. |

| Key Components | Fire doors, fire-rated walls/floors (compartmentation), firestopping, cavity barriers, intumescent coatings. | Fire alarms, smoke detectors, heat detectors, sprinkler systems, fire extinguishers. |

| Objective | Buys time for evacuation and for emergency services to arrive by slowing fire spread. | Provides early warning and initiates an immediate response to control the fire. |

| Human Interaction | Minimal. It performs its function automatically based on its physical properties. | Requires human action (evacuation, using an extinguisher) or automatic activation. |

While they operate differently, it’s clear they are two sides of the same coin, both essential for a building’s overall fire strategy.

To see how they work together, imagine a fire breaks out in a server room of a UK office block.

The active systems kick in first:

At the exact same time, the passive systems are already doing their critical, unseen work:

Without the passive ‘fortress’, the active ‘responders’ would be fighting a losing battle. The alarm would sound, but the escape routes would quickly fill with deadly smoke, putting lives at severe and immediate risk. This partnership is the absolute cornerstone of your responsibility under the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005.

To really understand passive fire protection, you need to see it as a complete system, not just a list of individual items. These components all work together to build fire resilience directly into the fabric of a building. For anyone with fire safety duties in a UK property, understanding these elements is the first step toward managing them properly.

Let’s break down the key PFP systems you’ll find in almost any commercial or residential building. We’ll look at what they do, where you’ll find them, and the common problems a fire risk assessment often brings to light.

Compartmentation is the absolute cornerstone of passive fire protection. The idea is simple but brilliant: divide a building into smaller, fire-resistant cells using special walls, floors, and ceilings. These barriers are designed to hold back a fire for a set amount of time, usually 30, 60, 90, or 120 minutes.

The goal is to trap a fire where it starts, stopping it from spreading through the building and, most importantly, protecting vital escape routes like corridors and stairwells. It buys precious time for people to get out safely.

Most failures here come from a simple lack of awareness. An electrician drills a hole for a new cable through a fire-rated wall but does not seal it correctly, creating a perfect pathway for fire and smoke to bypass the entire system.

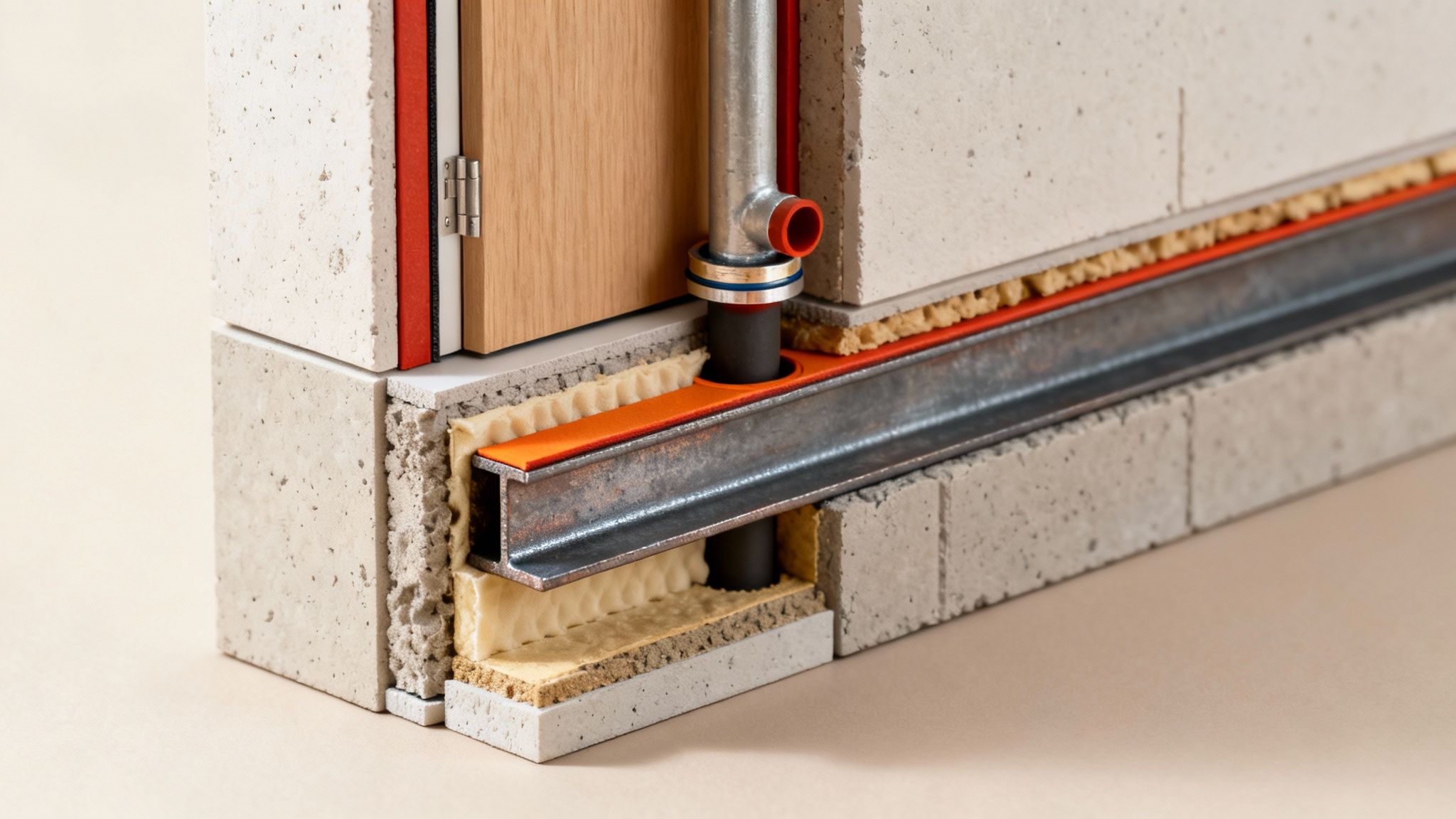

Fire doors are the moving parts within these fire compartments. They are highly engineered doorsets that, when shut, provide the same level of fire resistance as the wall they are fitted in. For a fire door to work, the entire assembly has to be right: the door leaf, frame, hinges, latches, closer, and the intumescent seals around the edges.

A fire door is not just a heavy door; it’s a critical piece of life-saving equipment. If it’s wedged open, damaged, or the self-closer is disconnected, it offers zero protection and makes the compartmentation useless.

When a fire breaks out, the heat triggers the intumescent strips around the door to swell up dramatically, sealing the gap between the door and its frame. This stops flames from getting through. If it also has cold smoke seals, it will block the toxic smoke, which is the biggest killer in fires. Keeping these doors in working order is a key legal duty, as we cover in our guide to UK fire door legislation.

Modern buildings are a maze of pipes, cables, and ducts running through walls and floors. Every single one of these openings, or penetrations, punches a hole through a fire-resistant barrier that has to be sealed.

Firestopping is the specialist job of sealing these gaps. This is not a task for DIY filler or a squirt of foam. Approved firestopping products like intumescent sealants, pipe collars, and fire batts are designed to expand when heated, plugging the hole and restoring the fire resistance of the wall or floor.

One of the most common defects found on a fire risk assessment is seeing general-purpose expanding foam used for firestopping. It offers no fire resistance and will burn away in seconds.

A building’s structural frame, especially if it’s made of steel, is extremely vulnerable in a fire. While steel does not burn, it loses its strength very quickly at high temperatures, which can lead to a catastrophic collapse.

Protecting the building’s skeleton is a crucial PFP job. It’s usually done in one of two ways:

A key check during an inspection is to ensure this protection has not been damaged or even removed during later refurbishment work.

Modern design loves using glass for walls and partitions. The problem is that normal glass provides virtually no fire resistance and will shatter almost instantly when exposed to the heat of a fire.

Fire-resisting glazing is a specialist product that can hold its own against fire for a set period, just like a solid wall can. It allows for open, light-filled spaces while still forming part of a fire compartment. You’ll often see it in fire doors with vision panels or in office partitions along an escape corridor.

Many buildings, particularly in the UK, are built with hidden voids and cavities inside walls, floors, and roof spaces. In a fire, these empty spaces can act like hidden chimneys, allowing flames and smoke to spread unseen throughout the entire property with frightening speed.

Cavity barriers are seals installed inside these concealed voids to chop them up into smaller, manageable sections. They’re usually made from materials like mineral wool and are placed at strategic points to stop fire from spreading undetected. Getting their installation right is vital—it’s what prevents a small, contained fire from becoming a full-blown disaster.

Knowing what passive fire protection is and how it works is only half the battle. The other, far more important part, is understanding your legal duty to maintain it. This responsibility is not optional; it’s a core requirement of UK fire safety law.

The Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005 places this duty squarely on the shoulders of the ‘Responsible Person’. This could be a landlord, an employer, a managing agent, or anyone with control over a property.

The Order is crystal clear: all fire safety provisions, including PFP, must be “subject to a suitable system of maintenance and are maintained in an efficient state, in efficient working order and in good repair.”

This is an active, ongoing duty. It is not a one-off check after a building is constructed or a simple box-ticking exercise. It means you must make sure that the fire doors, firestopping, and compartmentation in your building work effectively for its entire lifespan.

As the Responsible Person, your legal duties for PFP are non-negotiable. You are required to ensure the fire safety measures within your premises are fit for purpose. This means you need a solid grasp of your building’s PFP strategy and must take active steps to preserve it.

Your fire risk assessment is the cornerstone of this entire process. It must identify the PFP measures in place, assess their condition, and highlight any weak points that could put people at risk. Ignoring a damaged fire door is not just a maintenance issue; it is a direct breach of the Fire Safety Order.

Let’s think about a real-world scenario. A tenant in a commercial unit gets new data cabling installed, and their contractor drills unsealed holes through a fire-rated wall. As the building’s Responsible Person, it is your duty to have procedures in place to manage this kind of work and inspect it afterwards. If you do not, the building’s fire compartmentation is compromised, and you are the one who is legally accountable.

The legal fallout from neglecting PFP maintenance can be severe. The Fire and Rescue Service has the power to inspect your premises and will not hesitate to take action if they find problems.

Common enforcement actions for PFP failures include:

Imagine a routine fire safety audit reveals that several fire doors have been wedged open or their self-closers have been removed. This simple but common failure could easily trigger an enforcement notice, forcing you into immediate and costly repairs to bring the building back into compliance.

The scope of these duties was hammered home by the Fire Safety Act 2021. This legislation clarified that the Responsible Person’s duties under the Order also cover a building’s structure and external walls, including doors and windows. This was a direct response to the failings identified in the Grenfell Tower tragedy, underlining just how critical properly maintained building envelopes are.

Ultimately, maintaining PFP is about more than just avoiding fines. It’s a fundamental part of providing a safe environment for your employees, residents, or visitors.

It’s a common mistake to think of passive fire protection as a ‘fit and forget’ solution. The reality is, its effectiveness can be seriously undermined by everyday wear and tear, building work, or even simple maintenance tasks. A cable fitter drilling a new hole or a fire door constantly propped open can render a multi-thousand-pound system completely useless in an instant.

As the Responsible Person for your building, you have a legal duty to make sure these systems are properly maintained. While you’ll need accredited professionals for specialist repairs, carrying out your own regular visual inspections is a massive part of proactive fire safety. It empowers you to spot potential failures long before they become a serious risk.

You do not need to be a PFP expert to spot the obvious problems. Just by walking your property regularly with a critical eye, you can identify many of the common defects a professional fire risk assessor looks for. This simple habit can make a huge difference to the safety of your building.

Use this checklist as a starting point for your routine checks:

Here’s the key thing to remember: even minor-looking damage can have major consequences. An unsealed 10mm hole can allow a shocking volume of toxic smoke to pour through, jeopardising an entire escape route in minutes.

The need for this kind of vigilance is backed up by official data. In a recent twelve-month period, UK Fire and Rescue Services conducted 49,835 fire safety audits. Worryingly, only 58% of these achieved a satisfactory outcome, the lowest rate since 2011, often due to failures in passive fire protection. You can read more about these fire prevention and protection statistics on GOV.UK.

During professional fire safety inspections, our assessors frequently find critical PFP failures that property managers have walked past for years. These issues are often subtle and build up over time from unmanaged building work or poor maintenance.

Here are some of the most common hidden problems we find:

This is a critical point that can’t be stressed enough. Your role as the Responsible Person is to identify potential issues through these visual checks; it is not to fix them yourself. Passive fire protection is a highly specialised field governed by stringent standards and product testing.

Using the wrong materials or an incorrect installation method will completely negate the fire resistance you think you have. This not only fails to protect people but also leaves you legally exposed and in breach of the Fire Safety Order.

Always, always engage a competent, third-party accredited contractor for any PFP remediation work. A credible specialist will be able to prove their competency, use the correct certified products, and give you the proper documentation and certification for the completed work. This paperwork is vital evidence that you’ve exercised due diligence in keeping your building safe.

Right, we’ve covered a lot of ground on passive fire protection. We’ve established it’s the built-in, non-negotiable backbone of your building’s fire safety strategy. It’s there to protect lives, save your property from catastrophic damage, and keep you compliant with your legal duties under the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005.

The single most important thing to remember is that PFP is not a ‘fit and forget’ feature. It demands active, ongoing management from you as the Responsible Person. Ignoring it simply is not an option and can lead to hefty fines, enforcement action, and an unacceptable level of risk to everyone in your building.

So, with all that in mind, it’s time to turn theory into practice with a clear action plan.

To move forward with confidence, your next steps need to be methodical and, crucially, written down. This is not just about ticking boxes for compliance; it’s about actively managing the safety of your building and the people inside it.

Think of this process not as fault-finding, but as a way to gain certainty and show you’ve done your due diligence. A proper evaluation gives you a clear, documented picture of your property’s safety status and the peace of mind that comes with it.

Here’s a simple, three-step plan to get you started:

This section tackles some of the most common, practical questions that landlords, business owners, and property managers ask about passive fire protection. The answers are designed to be clear and straightforward, reinforcing the key duties we’ve covered in this guide.

Passive fire protection should be formally reviewed as part of your regular fire risk assessment. For most UK commercial and multi-occupied residential properties, this means at least annually, or whenever you make significant changes to the building.

But do not just wait for the annual assessment. You should be doing your own visual checks far more often, especially after any building work or maintenance has taken place. If you find any defects, they must be fixed immediately by a competent professional to ensure you stay compliant with the Fire Safety Order.

Absolutely not. Repairing passive fire protection is a specialist skill that demands certified products and precise installation methods. Any remedial work, whether it is fixing a damaged fire door, applying firestopping around new cables, or patching a fire-rated wall, must be carried out by a competent, third-party accredited contractor.

A DIY repair using the wrong materials, like generic expanding foam from a hardware shop, will completely void the system’s fire rating. This not only fails to protect your occupants but also leaves you legally exposed and non-compliant. Always, always demand certification for any PFP remediation work.

The ultimate legal duty always falls to the ‘Responsible Person’ as defined by the Fire Safety Order. While a commercial lease will detail the day-to-day maintenance responsibilities, this duty often sits with the employer or the person in control of the premises.

In a multi-let building, this responsibility is usually shared. The landlord is generally responsible for the common areas and the building’s core structure, while each tenant is responsible for maintaining the PFP within their own unit. It is crucial that your lease agreement outlines these duties clearly and unambiguously to avoid any confusion.

Ensuring your property’s passive fire protection is correctly specified, installed, and maintained is a critical legal duty. If you have any doubts about your PFP systems, a professional fire risk assessment is the essential next step. Contact HMO Fire Risk Assessment today to book a comprehensive assessment and gain clarity on your compliance obligations. Visit us at https://hmofireriskassessment.com to secure your property and protect its occupants.

A fire door inspection is a systematic, detailed check to verify that a fire doorset is functioning correctly and meets all legal UK standards. It...

As a landlord or manager of a House in Multiple Occupation (HMO) in the UK, you are legally responsible for ensuring your property’s fire doors...